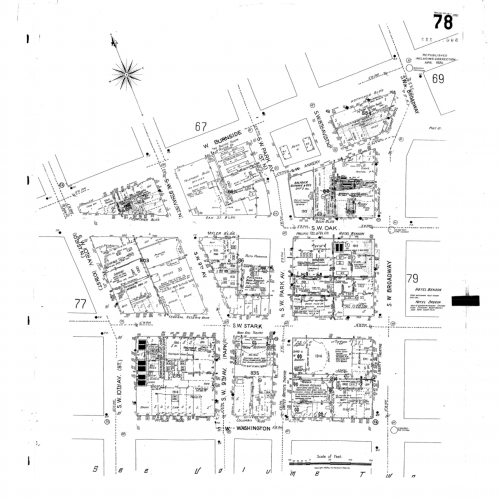

Portland, Oregon’s famed Majestic Theater was opened on the corner of Washington and Southwest Broadway in 1911. The theater was owned by Edwin Jones, a Seattle business man who moved to Oregon to pursue the exhibition industry. Though Jones was new to the area when opening the Majestic, he made quite a name for himself in the coming years, becoming known for his theater residing in the “same house, same location for longer than any other exhibitor in Portland.”

The Majestic also became known for being one of the first two theaters on the Pacific Coast to add live musical accompaniments to the silent films at this time. During this time, The Peoples Amusement Company monopolized on the film industry, leaving other theaters to compete for audiences. Edwin Jones’ rose to the occasion by introduce organ music playing to the silent films and launched the first organ music accompaniment on the same day at The Star (the theater across the street).

Mr. Jones became known to be a man that took pride in theaters and film. He put in a great deal of effort into pre-screening all films before showing them at the Majestic. Scenes that could be seen as controversial were cut from the film. Yet, other films that officials felt were controversial, such as the film “Sapho”, he found beauty and value in and had no shame in publicly fighting for the right to show it. Furthermore, he introduced unseen films to the Portland theater scene. Films such as “The Fall of Troy”, which was a two-reel film and cost $150 per week to rent – a large price to pay during this time.

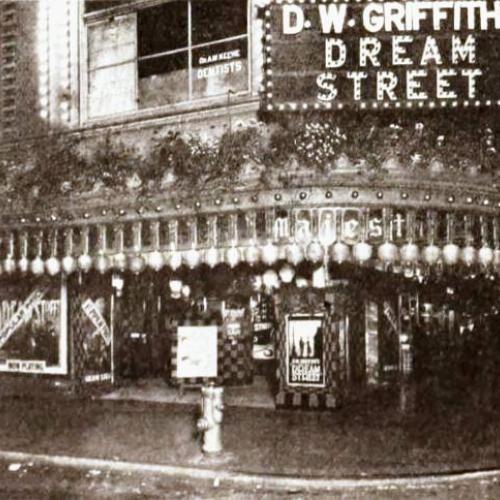

Edwin Jones was no doubt a businessman who shared the love of exhibition. Because of this, he was accustomed to spending the money needed to create a grand experience. He embraced the transition when nickelodeons and movie storefronts were no longer meeting the needs of the audiences and the development of movie palaces were born. Mr. Jones built The Majestic as a movie palace in 1911 for $62,000, seating 1,050 audience members. The Majestic was built in line with movie palaces that possessed grand architectural decoration and were meant to make the audience feel transported into an upscale, imaginative atmosphere.

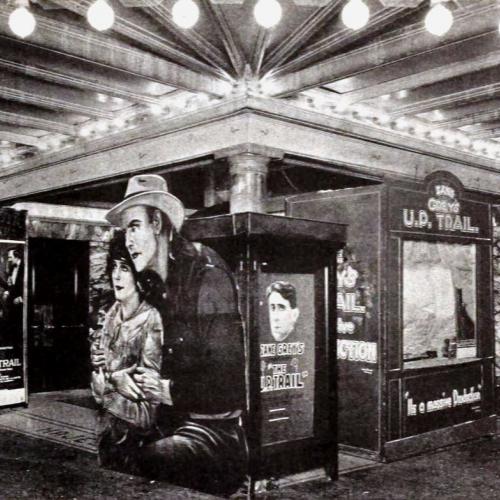

Looking at historic theater marques, they are most commonly built as overhangs or canopies at the entrance of theaters that hold signage. These marques would draw attention, advertise the next showings as well and provide coverage for audiences waiting for tickets. What the Majestic Theater did with the architecture of their marque was quite unique. They took advantage of their corner lot and the foot traffic that took place at that corner by guiding the foot traffic through the corner of their building. By carving out the corner of Washington and Broadway and creating a covered vestibule they were able to create a cross section for shopper to now experience a gallery-like settling that displayed the current and upcoming acts and movie adds. While most theaters save the grand architectural details for the interior of these movie palaces, the Majestic was able to entice local shoppers or pedestrians by bringing the indoor experience, outside on this busy street corner. The theater lined the entire rounded corner with bright lights, drawing in crowds from all over.

Advertising was extremely important to Edwin F. James, and his manager, Frank Lacey (1). While showing a comedy feature by Mr. and Mrs. Carter DeHaven called Their Day of Rest, Frank Lacey took an ad from a newspaper in the film, and put it in a real newspaper. Quite the practical joke. Especially because the ad read "A cook, $100 a month, every afternoon off, use of family vehicle on Sunday," These were tantalizing requests in 1919. $100 a month is a lot of money. In fact, a person applying for the job wrote, "If I ever earned $100 a month, I don't know what I would do, but I am willing to try it and see." This ad worked as people were contacting Majestic theater in every way they could to get this one of a kind job. Little did they know, Frank Lacey was playing a practical joke on them. The newspaper article snippet goes on to say that the ad had caused a lot of talk throughout the town. And Frank Lacey is quoted saying, "It pays to advertise."

One can imagine what a staple this theater was in the community. Edwin Jones’ love for exhibition drew in crowds from all classes to enjoy film and live musicians for 18 long years before the theater closed in 1929. The theater was later bought and re-opened by Theater Artist Union.