The Orpheum Theatre in Portland, Oregon, opened in 1913 and quickly became a central hub for entertainment, featuring a blend of vaudeville performances, grand operas, and later, motion pictures. Its programming was designed to appeal to a wide audience, with well-known performers and a mix of live shows and films. The theater adapted to the evolving entertainment landscape, transitioning from vaudeville to cinema as the popularity of motion pictures grew in the early 20th century. Special events, lectures, and other cultural offerings filled the theater’s schedule, ensuring its status as a cultural landmark in Portland.

Promotional strategies played a significant role in the Orpheum’s success, with newspaper ads, exterior signs, and collaborations with local businesses like Knight’s Big Shoe House helping to draw in audiences. Unique events such as the “Cinderella Contest” encouraged public participation and increased visibility for the theater. Despite facing competition from other local venues and the rise of leisure activities, the Orpheum remained a popular destination by offering diverse programming and adapting to the changing tastes of its audience. Additionally, it navigated the challenges of censorship and regulation, ensuring it complied with moral codes while maintaining broad appeal. Through these strategies and its ability to evolve, the Orpheum cemented its place in Portland's entertainment history.The Orpheum Vaudeville Theatre in Portland was a prominent venue for musical performances, featuring a diverse array of acts ranging from operatic singers to popular contemporary musicians of the early 20th century. Music played a central role in vaudeville entertainment, often serving as both a standalone attraction and an accompaniment to theatrical performances. Despite the growing popularity of motion pictures and changes in the entertainment industry, the Orpheum maintained relatively stable ticket prices, ensuring accessibility for a broad audience. This pricing strategy was consistent with vaudeville’s emphasis on offering affordable, high-quality entertainment to the working and middle classes. By keeping admission costs steady, the theater fostered a loyal audience base and sustained its reputation as a premier destination for live musical and theatrical acts. This balance of musical variety and economic accessibility contributed to the Orpheum’s lasting influence in Portland’s entertainment history.

Barnet Marcus Priteca, a Scottish-born architect, designed the Orpheum Theatre in Portland as part of his extensive work on vaudeville and movie palaces across the United States. Known for his long-standing collaboration with theater magnate Alexander Pantages, Priteca specialized in creating opulent yet functional entertainment venues that catered to the evolving tastes of early 20th-century audiences. His design for the Orpheum reflected the grandeur and elegance characteristic of his work, solidifying his reputation as a leading theater architect of his time (Image C).

In 1913, the Orpheum Theatre in Portland collaborated with Knight’s Big Shoe House to host a unique promotional event known as the “Cinderella Contest.” The competition invited women over the age of eighteen to try on a specially selected slipper, with the promise that whoever successfully fit into the shoe would win two box seats at the theater. This marketing strategy capitalized on the popular fairy tale motif, drawing public interest and engagement. However, despite numerous attempts, no woman was able to fit into the slipper, resulting in an unclaimed prize. The contest not only served as a publicity stunt for both the theater and the shoe store but also reflected early 20th-century promotional tactics that merged entertainment with commerce. Ultimately, this event highlights the inventive yet sometimes impractical nature of early advertising strategies in the vaudeville era. On April 29, 1915, the Orpheum Theatre temporarily closed its doors for the summer, following the directive of its owner, Mr. John W. Considine, who managed the theater chain from Seattle. This seasonal closure was a strategic decision likely influenced by audience patterns and financial considerations within the vaudeville circuit. When the theater reopened in the fall, it began transitioning toward film exhibition, reflecting broader industry trends as motion pictures gained popularity. This shift demonstrated the Orpheum's adaptability in response to the changing entertainment landscape of the early 20th century. The decision to incorporate film screenings marked a pivotal moment in the theater's history, aligning it with the emerging dominance of cinema over live vaudeville performances(images A/B/D/E).

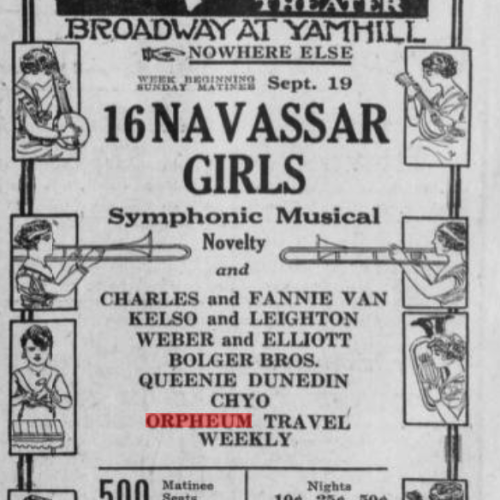

The Orpheum Theatre’s programming strategy was carefully designed to maximize audience appeal and financial success, relying heavily on star power to attract patrons. By booking well-known vaudeville performers, such as celebrated musicians, comedians, and magicians, the theater ensured a steady stream of eager attendees, capitalizing on the public’s fascination with established entertainers. A key component of its business model was the deliberate pricing strategy, which involved lowering ticket prices for shows that had already played in San Francisco. This approach allowed the theater to gradually introduce high-quality acts to Portland audiences while minimizing financial risk. By starting with reduced prices, the Orpheum’s management aimed to build momentum, cultivate a loyal customer base, and eventually justify higher ticket costs as demand grew. This calculated approach to programming and pricing reinforced the Orpheum’s role as a major cultural institution in Portland’s early 20th-century entertainment scene. (Image F/G)