Since the emergence of cinema, local and federal governing bodies have had a say in what actually makes it to the silver screen. The roots of cinema established the art form as a family-friendly way to keep people out of trouble. Any sort of film promoting or even alluding to behaviors which don’t align with these values got the chop. However, while promoting itself as in the best interests of the people, the box office turnouts for heavily censored films often showed otherwise.

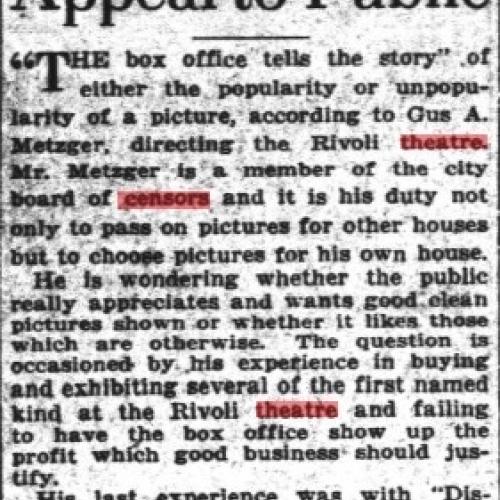

Such is the case with Gus A. Metzger, directing the Rivoli Theater of 371 Washington Street, Portland, Oregon in 1920. Gus is quoted with saying, “The box office tells the story”, which demonstrates a clear understanding of a successful business model. While Metzger, like all other critics of the time, wanted to maintain a “clean” nature within film, he understood that the audiences may hold different sentiments, and that the best way to determine so was through the box office turnout.

Metzger’s experiment was marked by the exhibition of multiple heavily censored productions, Last of the Mohicans (1920) and Mother of Mine (1921) all failing to turn a sizable profit of which a well run business would generate. While Metzger’s showings proved the majority audience’s reluctance to see “clean” pictures, he didn’t adapt, doubling down with the showing of Disraeli (1921), starring acclaimed actor George Arliss. While those in attendance enjoyed the acting and clean nature of the production, the exhibition was also dubbed a “flop”.

Metzger’s actions proved that while he and other exhibitors understood consumers were ultimately the ones who dictated a business’s success, he and many theater owners at the time sealed their fates through their own reluctance to adapt.